Ben X

In what would usually be referred to as ’the real world’, Ben is a Belgian (Flemish) teenager; lonely, full of anxiety, practically mute, and autistic. Is he anxious and silent because he is autistic? Well, partly, yes. But it is also because he is treated ever so horribly by his classmates who tease him, bully him, beat him, drug him, and humiliate him. Despite having loving and caring parents, and at least one kind and considerate teacher, Ben’s ‘real world’ existence is full of suffering; it is quite unbearable.

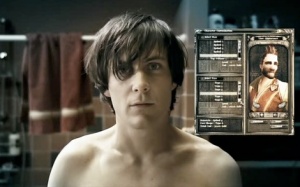

But in the virtual on-screen world of Archlord, he is Ben X; a hero, a skilled warrior, an esteemed and respected figure; and the fellow in battle, travel, and play to the equally skillful heroine who goes by the name of Scarlite.

“The princess of letters, on the other side of the land; who is always by my side when things get out of hand; who knows me without knowing my name; who could put me back together again; who could make me ‘sleep tight’.“

During the film, Ben constantly shifts back and forth between the two worlds he inhabits; master in one, victim in the other; admired in one, tortured in the other. Is it any surprise he prefers one over the other?

An excessive liking to video games is frequently framed as a problem; quite often, the word addiction is invoked. I don’t want to go into a debate about whether excessive gaming is really such a bad thing or not – I guess I just find it hard to generalize. In principal: yes, a healthy life should ideally consist of various kinds of stimuli, not just one. But if video games offer someone a place where they can finally shed their anxiety and have some much needed relaxation and fun, while socializing in ways that would otherwise simply be too overwhelming, frightening, or painful – I don’t know, who’s to say that’s wrong? But like I said, this isn’t the discussion I was going for. What I would like to talk about is the role that virtual worlds have in the lives of those who play it; the important role that is quite often misunderstood, and possibly unappreciated by others.

Tom Boellstorff is social anthropologist. Like many others, he has chosen to study a culture different than his own. It has its own rules, norms, values, and symbols. Like members of most other cultural groups, the members of his studied culture, too, have bodies and occupy a space. Except in this case, the bodies are avatars, and the space they occupy is the virtual world of Second Life. Years of bad rep by people who don’t quite understand this world have contributed to a conception of Second Life as offering a type of a shallow, worthless sociality; a fake. Boellstorff shows exactly the opposite: Second Life, and presumably any other virtual world, is as unequivocally social, and just as real as any other space where people live and act.

First, he says, let’s get rid of the useless distinction between real and virtual that only confuses things. Connections made online are every bit as real as the ones made offline; people make friends on chat rooms, meet life partners in virtual worlds, find support in discussion forums, and joke around with other people on twitter. What’s not real about any of these activities? Is it different than making a friend in a book shop, being on a date in a bar, or sitting in a therapist’s clinic? Of course it is different. But is it any less real? Nope. It’s mediated, yes. But hey, so is a phone conversation, and that hasn’t been said to be fake since probably a century ago. Once the landline has become widespread, and we became accustomed to it, we accepted it as a valid form of communication. Virtual worlds are not essentially different from the landline insofar as they are a means of communication; visually elaborate and creatively designed, yes (how is that a bad thing?), but merely a means of communications nonetheless.

So instead of talking about the real-world, when all we’re talking about is communication-that-isn’t-mediated-by-technology, let’s talk about the actual world instead, as the counterpart of the virtual world. Different as the actual and the virtual worlds may be, both are equally real.

So if we agree that the story is not that there is the real world on one hand and a fake world on the other hand, but that we are simply talking about two spheres of the real world, we might want to ask – what’s the relationship between the two? How does one relate to the other?

Try this explanation: the virtual and the actual are distinct, but they are not separate. What happens in the actual world shapes one’s experience of the virtual world, and what happens in the virtual world shapes our interpretation of the actual world. It’s basically a continuous two-way dynamic, with mutual effects. How is this outlook helpful? Well, we could say, for example, that Ben’s online experiences make him see his actual-life reality in a certain way – as compared to (compared to the virtual world, that is), rather than as simply is. This has both negative and positive consequences: it inspires in him hope, suggests strategies for improvement, and offers a reservoir of images for day-dreaming and fantasizing. But at the same time, it highlights reality (actual-world reality) at its poorest: a violent, cruel, uncompassionate existence, where people’s potential is not realized, and power is used for evil instead of good. At the same time, Ben’s offline existence affects his virtual-life: he uses his avatar to act out his emotions, to speak honestly to his friend, to exert courage, but also to show weakness.

In other words, Ben is not leading two separate lives; he lives one life, which is divided into two spheres. Ben uses relatively novel technology to do this, but other than that, is it really so unique? Think of a businesswoman, spending weekdays in the office and weekends with her family; think of an army commander who spends several months at home followed by several months in the battlefield; think of a football player – running and kicking on the pitch, then having dinner with his wife; think of how we all take holidays; isn’t it quite the same thing, at the bottom of it? Same world, different spheres of life; same person, different ‘selves’.

Also:

If Ben inhabits two spheres, and occupies two bodies, can he be said to be two people? Well I wouldn’t go that far, but I would definitely agree that Ben has two selves. Not a real one and a fake one, mind you, as we’ve already established that they’re both perfectly real. They are certainly different, though; so perhaps the better question would be to ask in what way his two selves are different. And in this respect, the most obvious difference between the living body and the digital body is that while the former can feel, hear, touch, taste, smell, and sense – the latter can’t; it is numb, indifferent, desensitized.

So the living body has the capacity for pleasure; but also for pain. We tend to idealize bodily pleasure, and lament its absence. But like Pink Floyd suggested, numbness can often be comfortable; particularly if the alternative is not pleasure, but pain and suffering.

Another important difference is this: there is only so much one can do to change their physical body; of course you can exercise, eat better, dye your hair, dress according to whatever fashion you like, and even have cosmetic surgery – but mostly, it’s a given. You keep what you draw. Your virtual body, on the other hand – now that’s just one big variable. You can choose your gender (with the body parts to go with it), your appearance; even your species! Feel like a pixie toddler today? A bi-sexual cross-gender giant? A carnivorous double-hump camel? You can be that. And you can play the part with confidence, because no one will accuse you of acting childlike when you should be acting like an adult; for acting masculine when you’re expected to be lady-like; for making jokes when situations calls for serious behaviour – or the other way around. In other words, you can just be yourself – silly as that may sound – when you’re a made-up character. Self-fashioning – self-creation even – are real possibilities in virtual worlds. They afford a type of creativity that goes beyond drawing on canvas, or writing words on paper – they afford creativity that can be utilized to design your very self. And for some people, particularly those whose physical existence is an endless and futile struggle to either conform to, or reject their expected social roles – to finally be able to choose the role that suits you, down to the very last detail – how appealing is that?

“In games you can be whoever and whatever you like. Here you can only be one person. The jerk you see in the mirror. I have to teach him everything. For example, I have to teach him to laugh. People like that. To ‘give them a smile’, as they say. Which means smiling when really there’s nothing to smile about. That’s how you create your own avatar.”

Get it? We create avatars in the actual-world all the time. Except it’s harder, and we get very little choice about what we want these avatars to be.

In his mind, Ben wishes for his two characters – his two selves – to unite. He can only fantasize how his virtual self would react in the actual-world events he is forced to cope with. If only Ben had Ben X’s strength, courage, swordsmanship, and way with words, his life would have been so much better. But he hasn’t; and it’s not. It’s as hard as anyone can imagine. Ben X might have it made; but Ben is miserable.

In one critical junction in the story, it seems as if at least one formidable achievement of Ben’s virtual self might finally be transported to his actual-world; the friendship and affection of his co-player, Scarlite. Her actual-world self is worried about his, and she’s coming on the train to meet him. But the embodied, actual-world version of Scarlite simply proves too petrifying for him to approach – he can’t even say hello. Then, at one tragic moment, the pain of Ben’s existence overwhelms him, and he decides to kill himself by jumping under a moving train. I’m not embarrassed to admit that I myself have confused the actual-world and the cinematic world, and cried “NO!!!” at the screen, with a very real voice, led by a very real emotion.

Ben doesn’t kill himself, luckily, though I dare speculate that his eventual decision to go on living was solely motivated by the movie makers’ concern for the intactness of their audience’s nearly-shattered hearts; not by any real motivation of the protagonist. In that sense, Ben’s delusion of Scarlite as a loving girlfriend is a classic Deus ex Machina (adequately defined in Wikipedia as “a plot device whereby a seemingly unsolvable problem is suddenly and abruptly resolved by the contrived and unexpected intervention of some new event, character, ability, or object” – isn’t that precisely what Ben’s delusion of Scarlite is?) In other words, if Ben were to kill himself, this would have been a devastating story, and yet a remarkably sincere one (it seems the true story on which the novel was based did, in-fact, end with suicide). Adolescent suicide is a real-world problem, so an honest cinematic depiction of it would not have been ill-suited. But as it happened, the makers of Ben X chose to convey the dangers and injustices of high-school brutality in a different way; through their protagonist’s somewhat playful ploy, tricking his community into believing he had committed suicide, and noting their collective conscience at work. To actually have their main character proceed to kill himself would, I believe, send the same message, but so much more powerfully.

But at any rate, Ben X offers quite a brilliant depiction, I thought, of an important part of the experience of being autistic. It’s not always charming naivety, childhood innocence, good-naturedness, and a wholesome dash of some much-called-for honesty; instead, sometimes, it’s about suffering, anxiety, depression, distress, loneliness, and even suicidal thoughts. Aren’t these very often what autistic adolescents must cope with, in a society where antipathy, intolerance, and plain cruelty are all too common?

“Then it was time for truthfulness. Shamefulness, painfulness.” Indeed. Sometimes it is.

What do you think?

Related Posts: